There are two endings to Blind Mountain. In the censored Mainland Chinese version, the police comes and rescues the female protagonist from her rural prison. In the version for international release, which is the one I watched, the girl grabs the knife closest to her and, in a climactic eruption of violence, stabs her “husband” who is stopping her from leaving. Then, the screen fades to black.

From leaving what? A marriage that she was sold into, an entire village that is complicit in the trafficking of women, the stifling despair of being surrounded by other women—some held captive for years and resigned to their fates—who persuade her that “All women go through this”, the insular traditions of female infanticide and a family that treats her like a reproductive vessel, much like what they expect of the piglets in their shed.

This is the well-known reality within China: the trafficking of hundreds of thousands of women, sold to rural bachelors as brides. It’s a decades-old crisis that has been dissected by sociologists and then largely ignored by society until occasional sensational headlines surface (take, for instance, the story of “model teacher” Gao Yanmin). Much has been said, little has been done, much less is understood. Why are hundreds of thousands of these tragedies enacted across the country, year after year, with negligible change?

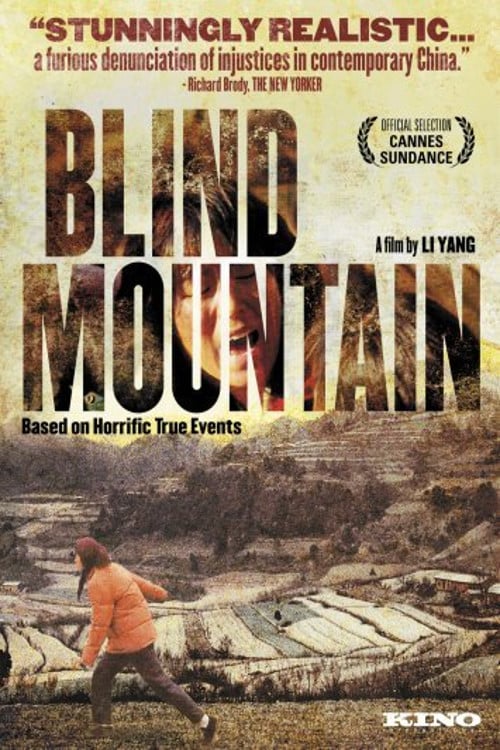

As one of the rare few Chinese movies about the endemic problem of trafficking, Blind Mountain cuts through the noise, social analysis and propaganda to brutally present the ordeal of the female protagonist. On a search for employment, college graduate Bai Xuemei is duped and abducted to the rural mountains, where she is sold to a farming family. A purchased womb for “husband” Degui, a middle-aged illiterate farmer, Xuemei resists and is raped, beaten and impregnated. Again and again, she attempts to run away. Each time, she has to scale the silent mountains, tearing through the eerily atmospheric beauty of unspoiled nature. Every attempt—nail-bitingly painful to watch—comes up against the cruelty, apathy and tacit surveillance of the villagers, many of whom have bought wives themselves and collude with one another to prevent any woman from escaping. As the story races to its explosive conclusion, the movie puts an entire society—not just a family or a village—on trial.

So matter-of-fact and unembellished is the narration (with many takes masterfully shot with a hand-held camera) that vile moments arrive without any spectacle. Despite the raw, economical style, the emotions run so thick and palpable that I had to pause the movie twice just to breathe. Stripped to the narrative bone, this movie horrifies and haunts more than any slasher pic.

The idea of “blindness” runs throughout Director Li Yang’s trilogy: Blind Shaft (2003), Blind Mountain (2007) and Blind Way (2017). Each respectively deals with the plight of laborers in illegal mines, women sold into the mountains as wives and disabled children prostituted in illicit begging rings. Just because we can’t see it doesn’t mean these crimes don’t exist. They are happening right around us.

Who is blind here? It’s easy to say the villagers due to their ignorance and atrocities. But so is the law—blind in its (lack of) enforcement, which persecutes only the traffickers and not the buyers. In one scene, a provincial official visits the village and is pleased to see a pastoral idyll; all the trafficked women have been hidden, obscured from the picturesque. I wonder if this is blindness by choice. What the state desires is not the gritty truth but a manufactured mirage of prosperity. As for citizens, especially those in cities, it’s much easier to believe what the state dictates than to confront the persistent monstrosities happening in the country’s underbelly. So it is society too that has turned a blind eye. One is left with unabating despair.

What deeply frustrates and crushes is the moral vacuity—an eroding sense of inertness—of these stagnant backwaters. A deep, pervasive sense of loss and impotence drifts over the villagers, even the men who rape and beat their bought wives. Each lash of violence seems to be a bitter retaliation against a world that has left them behind and given them few choices of living with dignity. Severed from the country’s economic growth and the upbeat ‘Chinese dream’, these men sicken yet sadden.

I want to tell you that this movie spares us nothing. But I know that reality is only harsher and bleaker than the images. How long more will this latent moral crisis simmer? When will it reach the tipping point? Until then, our conscience can only atrophy.

作家有多大的想象力都无法超越现实本身的疯狂、炸裂和传奇。终于到了这一天,现实的荒诞和作家的想象赛跑。最后赢的是中国现实输的是中国作家的想象力。

No matter how expansive the imagination of the pen, there is no surpassing reality’s own outrageous explosiveness and notoriety. So we’ve reached this day: the absurdity of the real races literary imagination. And at last, it is China’s reality that wins and China’s authors who lose. (my translation)

Yan Lianke 阎连科

I think the quote on the *apocalyptic objectivity* associated with this suprahistorical perspective by Foucault is relevant here.

… suprahistorical perspective: a history whose function is to compose the finally reduced diversity of time into a totality fully closed upon itself; a history that always encourages subjective recognitions and attributes a form of reconciliation to all the displacements of the past; a history whose perspective on all that precedes it implies the end of time, a completed development. The historian’s history finds its support outside of time and pretends to base its judgments on an *apocalyptic objectivity.* This is only possible, however, because of its belief in eternal truth, the immortality of the soul, and the nature of consciousness as always identical to itself. Once the historical sense is mastered by a suprahistorical perspective, metaphysics can bend it to its own purpose, and, by aligning it to the demands of objective science, it can impose its own “Egyptianism.”

LikeLike

Hmm when I read 网络小说 on 人贩子 I never really thought about why this phenomenon occurs, I’ll be super angry at these rural mountain villages and think that they should just disappear off the surface of the earth, and then its a heroic story when someone rescues the abducted victims or they manage to save themselves and everybody claps and forget about the issues from the root ><

Huh but then how? Relocate these villages and reeducate meh aish

I think I'll go watch 盲山 soon, fits my emo mood these days

LikeLiked by 1 person

you’re absolutely right kaikai… there’s no easy solution – it’s a bunch of different factors (eg one child policy, gender imbalance in rural areas, increasingly expensive marriage traditions like 彩礼 which many bachelors can’t afford, the extreme wealth inequality between rural-urban, the government closing one eye…) that have led to an entrenched, inhuman phenomenon and our flares of outrage seem so cheap and ineffectual in the face of this

go watch!!! and we can talk about it ><

there was a nytimes review that said, “it’s a reminder that art sometimes keeps the truth alive far better than the news” – this movie does exactly that

LikeLike